From the Hawthorne Tree

Bits and bobs about my cousin, Nathaniel Hawthorne

Read/Post Comments (4)

"Every individual has a place to fill in the world, and is important, in some respects, whether he chooses to be so or not."

~ Nath'l Hawthorne, Oct. 25, 1835, American Note Books

The Day Hawthorne's Home was Burgled

Nathaniel Hawthorne, the American author, kept notes of most things he did and saw and experienced. We are lucky enough to have these notes published and made available to his followers in the public. Some of them are quite interesting and may be enjoyable for you to read in snippets here.

The following excerpt is from Hawthorne's English Note Books and is entered under "1857" in the Contents page.

As you may or may not know/remember, I am related to Hawthorne, being from the Ingersolls on my mother's side and Hawthorne's cousin, Susannah Ingersoll, being the daughter of the owner of what would later be called The House of the Seven Gables. So we are cousins, Nathaniel and I.

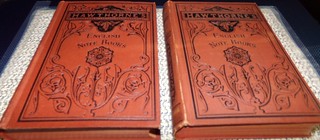

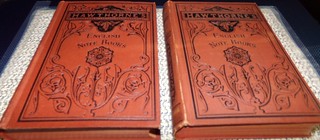

I've just obtained Vol. I and Vol. II of his "English Note Books" published in Boston in 1876. I've just started reading them but find I am hopping all over the place in the books, picking out various dates to read about; it's like a diary to read and Hawthorne was quite diligent at keeping up with his journals.

Just FYI, his three children were Unna, Julian, and Rose.

In the entry below, you will see that he relates the time when his home in Liverpool, England (he was the American consulate there from 1853-1858) was burgled, and I found his description of the whole affair just lovely! Especially the last sentence in it!

I love that last line! It says so much about the author.

Cheers for our long-gone cousins!

Bex

The following excerpt is from Hawthorne's English Note Books and is entered under "1857" in the Contents page.

As you may or may not know/remember, I am related to Hawthorne, being from the Ingersolls on my mother's side and Hawthorne's cousin, Susannah Ingersoll, being the daughter of the owner of what would later be called The House of the Seven Gables. So we are cousins, Nathaniel and I.

I've just obtained Vol. I and Vol. II of his "English Note Books" published in Boston in 1876. I've just started reading them but find I am hopping all over the place in the books, picking out various dates to read about; it's like a diary to read and Hawthorne was quite diligent at keeping up with his journals.

Just FYI, his three children were Unna, Julian, and Rose.

In the entry below, you will see that he relates the time when his home in Liverpool, England (he was the American consulate there from 1853-1858) was burgled, and I found his description of the whole affair just lovely! Especially the last sentence in it!

March 1st, 1857.--On the night of last Wednesday week, our house was broken into by robbers. They entered by the back window of the breakfast-room, which is the children's school-room, breaking or cutting a pane of glass, so as to undo the fastening. I have a dim idea of having heard a noise through my sleep; but if so, it did not more than slightly disturb me. U-- heard it, she being at watch with R---; and J-----, having a cold, was also wakeful, and thought the noise was of servants moving about below. Neither did the idea of robbers occur to U--. J-----, however, hearing U-- at her mother's door, asking for medicine for R---, called out for medicine for his cold, and the thieves probably thought we were bestirring ourselves, and so took flight. In the morning the servants found the hall door and the breakfast-room window open; some silver cups and some other trifles of plate were gone from the sideboard, and there were tokens that the whole lower part of the house had been ransacked; but the thieves had evidently gone off in a hurry, leaving some articles which they would have taken, had they been more at leisure.

We gave information to the police, and an inspector and constable soon came to make investigations, taking a list of the missing articles, and informing themselves as to all particulars that could be known. I did not much expect ever to hear any more of the stolen property; but on Sunday a constable came to request my presence at the police-office to identify the lost things. The thieves had been caught in Liverpool, and some of the property found upon them, and some of it at a pawnbroker's where they had pledged it. The police-office is a small dark room, in the basement story of the Town Hall of Southport; and over the mantel-piece, hanging one upon another, there are innumerable advertisements of robberies in houses, and on the highway,--murders, too, and garrotings; and offences of all sorts, not only in this district, but wide away, and forwarded from other police-stations. Being thus aggregated together, one realizes that there are a great many more offences than the public generally takes note of. Most of these advertisements were in pen and ink, with minute lists of the articles stolen; but the more important were in print; and there, too, I saw the printed advertisement of our own robbery, not for public circulation, but to be handed about privately, among police-officers and pawnbrokers. A rogue has a very poor chance in England, the police being so numerous, and their system so well organized.

In a corner of the police-office stood a contrivance for precisely measuring the heights of prisoners; and I took occasion to measure J-----, and found him four feet seven inches and a half high . A set of rules for the self-government of police-officers was nailed on the door, between twenty and thirty in number, and composing a system of constabulary ethics. The rules would be good for men in almost any walk of life; and I rather think the police-officers conform to them with tolerable strictness. They appear to be subordinated to one another on the military plan. The ordinary constable does not sit down in the presence of his inspector, and this latter seems to be half a gentleman; at least, such is the bearing of our Southport inspector, who wears a handsome uniform of green and silver, and salutes the principal inhabitants, when meeting them in the street, with an air of something like equality. Then again there is a superintendent, who certainly claims the rank of a gentleman, and has perhaps been an officer in the army. The superintendent of this district was present on this occasion.

The thieves were brought down from Liverpool on Tuesday, and examined in the Town Hall. I had been notified to be present, but, as a matter of courtesy, the police-officers refrained from calling me as a witness, the evidence of the servants being sufficient to identify the property. The thieves were two young men, not much over twenty,--James and John Macdonald, terribly shabby, dirty, jail-bird like, yet intelligent of aspect, and one of them handsome. The police knew them already, and they seemed not much abashed by their position. There were half a dozen magistrates on the bench,--idle old gentlemen of Southport and the vicinity, who lounged into the court, more as a matter of amusement than anything else, and lounged out again at their own pleasure; for these magisterial duties are a part of the pastime of the country gentlemen of England. They wore their hats on the bench. There were one or two of them more active than their fellows; but the real duty was done by the Clerk of the Court. The seats within the bar were occupied by the witnesses, and around the great table sat some of the more respectable people of Southport; and without the bar were the commonalty in great numbers; for this is said to be the first burglary that has occurred here within the memory of man, and so it has caused a great stir.

There seems to be a strong case against the prisoners. A boy attached to the railway testified to having seen them at Birchdale on Wednesday afternoon, and directed them on their way to Southport; Peter Pickup recognized them as having applied to him for lodgings in the course of that evening; a pawnbroker swore to one of them as having offered my top-coat for sale or pledge in Liverpool; and my boots were found on the feet of one of them,--all this in addition to other circumstances of pregnant suspicion. So they were committed for trial at the Liverpool assizes, to be holden some time in the present month. I rather wished them to escape.

I love that last line! It says so much about the author.

Cheers for our long-gone cousins!

Bex

Read/Post Comments (4)

Previous Entry :: Next Entry

Back to Top