Thinking as a Hobby

3478560 Curiosities served

What You Probably Don't Know About Evolution

Previous Entry :: Next Entry

Read/Post Comments (1)

Via Slashdot, here's a pretty good article describing several areas of evolutionary theory that most of the general public either doesn't understand or doesn't know about (though there are some problems with the article).

The topics covered are:

I'd highly recommend reading the article if you're up for it, though I'd quibble with two points.

First, the author says:

This is kind of a cop-out. Evolutionary theory explains what happens in populations of reproducing organisms competing for resources and surviving selectively. But populations with variation don't come from nowhere...the original replicators need to be explained, and that's an issue that is very closely related to evolutionary theory. There are a number of theories, but none are extremely strong or well-supported, mostly due to the fact that finding fossilized bones is hard enough...but tiny, self-replicating molecules from billions of years ago aren't going to be preserved. That doesn't mean we shouldn't try to understand it, because the question is foundational to biology. Trying to clearly dissociate it from evolutionary theory is a bad idea, though.

Secondly, in discussing the state of knowledge on human origins, they refer to a talk by John Relethford, an anthropologist in the SUNY system. Maybe they misrepresent what he actually said, but a couple of the points they do mention sound strange.

He rightly points out that the upright posture of our ancestors preceded the expansion of our brains and most of the associated cultural elaborations, such as tool use. But he talks about a "delay" between the evolution of bipedalism and brain expansion:

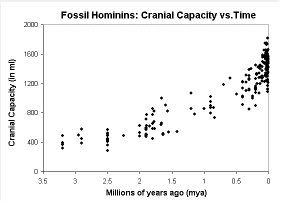

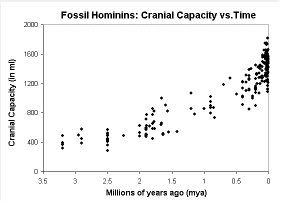

And the story includes this figure, with the caption "Big brains took their time":

So about 3 million years ago, the brains of human ancestors were about the size of modern chimpanzees. In the intervening 3 million years, the size of the brain roughly tripled. Pardon me for saying so, but I don't think that's a lazy pace. I'm no paleontologist, but I'd like to hear evidence of a change in brain capacity in any species that outstrips this one. It wouldn't shock me much if there were relative gains of this magnitude (though that would be interesting), but I doubt there are absolute gains in brain size this large.

Most literature I read on the expansion of brain in the hominin lineage describe it in terms like "explosion". I'm not sure why they're keen on representing it here like it was a slow creep.

And the follow-up point seems misguided as well:

This is interesting, because the increasing brain size and increasing metabolism of hominins is presented here as a trade-off. But another possibly way to look at it is that they create a positive feedback loop. In other words, increasingly larger brains allowed our ancestors to be cleverer in finding and acquiring food. More food equals more energy. More energy means more resources for building large brains. And so on.

Relethford presents the expanding brain as a cost only in terms of increased energy use, rather than being beneficial in acquiring more energy. A better example of a constraint would be pelvis size in hominin females. As hominin heads get bigger, mothers' pelvises are a real constraint on how big they can get.

Anyway, it's still a good article, showing that we really do know an awful lot about how many different trends in the history of life got started. The fossil record is not some dingy box of disparate bones. It's rich and illustrative, and getting richer all the time.

Evolutionary theory explains the trajectory of all life on this planet, past, present, and future, and to ignore or misunderstand it is to miss out on understanding where we came from and where we're going.

The topics covered are:

- The origin of life

- The origin of bilaterally-symmetrical organisms

- The origin of tetrapods (or, how animals invaded land)

- The origin of humans

I'd highly recommend reading the article if you're up for it, though I'd quibble with two points.

First, the author says:

One of these—the origin of life—isn't directly part of evolutionary theory, but is frequently associated with it by the public.

This is kind of a cop-out. Evolutionary theory explains what happens in populations of reproducing organisms competing for resources and surviving selectively. But populations with variation don't come from nowhere...the original replicators need to be explained, and that's an issue that is very closely related to evolutionary theory. There are a number of theories, but none are extremely strong or well-supported, mostly due to the fact that finding fossilized bones is hard enough...but tiny, self-replicating molecules from billions of years ago aren't going to be preserved. That doesn't mean we shouldn't try to understand it, because the question is foundational to biology. Trying to clearly dissociate it from evolutionary theory is a bad idea, though.

Secondly, in discussing the state of knowledge on human origins, they refer to a talk by John Relethford, an anthropologist in the SUNY system. Maybe they misrepresent what he actually said, but a couple of the points they do mention sound strange.

He rightly points out that the upright posture of our ancestors preceded the expansion of our brains and most of the associated cultural elaborations, such as tool use. But he talks about a "delay" between the evolution of bipedalism and brain expansion:

That delay might have been due to point five, the fact that cranial capacity increased very slowly and gradually over the course of human evolution.

And the story includes this figure, with the caption "Big brains took their time":

So about 3 million years ago, the brains of human ancestors were about the size of modern chimpanzees. In the intervening 3 million years, the size of the brain roughly tripled. Pardon me for saying so, but I don't think that's a lazy pace. I'm no paleontologist, but I'd like to hear evidence of a change in brain capacity in any species that outstrips this one. It wouldn't shock me much if there were relative gains of this magnitude (though that would be interesting), but I doubt there are absolute gains in brain size this large.

Most literature I read on the expansion of brain in the hominin lineage describe it in terms like "explosion". I'm not sure why they're keen on representing it here like it was a slow creep.

And the follow-up point seems misguided as well:

This illustrated Relethford's idea six: there's no free lunch. Any adaptation has a cost, and the advantages of expanding brain size were constantly balanced against the selective cost of a big brain's increased energy use and heat output.

This is interesting, because the increasing brain size and increasing metabolism of hominins is presented here as a trade-off. But another possibly way to look at it is that they create a positive feedback loop. In other words, increasingly larger brains allowed our ancestors to be cleverer in finding and acquiring food. More food equals more energy. More energy means more resources for building large brains. And so on.

Relethford presents the expanding brain as a cost only in terms of increased energy use, rather than being beneficial in acquiring more energy. A better example of a constraint would be pelvis size in hominin females. As hominin heads get bigger, mothers' pelvises are a real constraint on how big they can get.

Anyway, it's still a good article, showing that we really do know an awful lot about how many different trends in the history of life got started. The fossil record is not some dingy box of disparate bones. It's rich and illustrative, and getting richer all the time.

Evolutionary theory explains the trajectory of all life on this planet, past, present, and future, and to ignore or misunderstand it is to miss out on understanding where we came from and where we're going.

Read/Post Comments (1)

Previous Entry :: Next Entry

Back to Top