1481762 Curiosities served

Purple Stains, Purple Prose

Previous Entry :: Next Entry

Read/Post Comments (3)

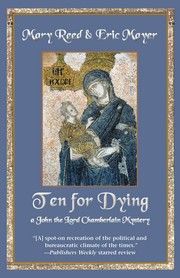

If not for Robert Rosenwald and Barbara Peters, publisher and editor-in-chief respectively of Poisoned Pen Press, I doubt I would ever have seen my name on the cover of a novel. The more I learn about the publishing industry, the more convinced I am that a Byzantine eunuch is (and forever will be) as welcome at a big New York publishing house as a Nestorian heretic at the Great Church in Constantinople.

I'm grateful to have books in print. The fact that our books are published gives me an excuse to do my bit for them. I enjoy writing. Concocting stories and manipulating words is great fun, but to me the object of the game is to communicate with an audience. Without the audience PPP finds for us, composing books would be a pointless exercise, long since abandoned.

Oddly enough, years before Robert Rosenwald assisted my writing efforts, his great-grandfather Julius did the same.

It happened in 1978, while I was living in Brooklyn, New York. I was an impoverished law student, a frustrated writer whose goal of having a novel published by the time he was twenty-one (didn't we all have such goals?) hadn't quite worked out. The only writing I was doing was for fanzines and even that frustrated me. I desperately wanted to publish my own fanzine.

The fanzines I'm talking about were, and are, amateur publications, without professional pretense, produced merely for amusement. The sort I wanted to put out were typically filled with short essays and bits of personal trivia. They were distributed by mail for free. Readers, many of whom published their own 'zines, would send letters of comment which would be printed at the end of each issue.

Think "slow paper blogs."

Most fanzines of that era were printed by mimeograph, a device far beyond my limited means -- I drank Fox Head beer because it was 99 cents a six pack.

I spent considerable time riding subways and braving unfamiliar alleyways to search dimly lit second-hand shops for the means to further my writing ambitions. There must have been a functional, affordable, used mimeograph hiding somewhere in the five Boroughs, but I couldn't find it.

The scarcity of mimeos wasn't entirely surprising because that printing technology had already become obsolete. In a world with photocopy machines, who wanted to struggle with wax stencils and tubes of ink...aside from a student who was forever looking under the sofa cushions for a fourth quarter to buy Fox Head, never mind the rolls and rolls of quarters -- riches beyond imagining -- needed at a self-serve copy machine?

Thinking of obsolescence, I had the idea to consult the Sears catalog. Sears, I had been told, kept everything in stock forever. If you had purchased a pot-bellied stove from Sears in 1908, you could still order parts.

Sure enough, the office equipment section of the catalog contained a virtual museum display of printing processes through the ages. I couldn't afford the mimeographs, of course, or even the ditto machines, although I eventually scraped together enough change to buy the hand-cranked gravity-fed spirit duplicator -- the same model Gutenberg used while he was tinkering with his printing press.

What caught my eye was the hectograph kit.

The hectograph process antedates fossilization. A master copy, upon which one has drawn or written in a special ink (specially designed never to come off any flesh it encounters) is pressed onto a gelatin pad -- essentially very hard Jell-O. The ink is absorbed into the pad. When the master is removed and blank sheets are placed on the gelatin, one by one, the pad releases a bit of ink. A hectograph will only make about fifty copies of diminishing quality, not counting the purple stains on one's skin, which show up in the strangest places. Whoever named the hecto (hundred) graph was an optimist. Or maybe the hecto is actually short for "heck" which is short for "Hell, why I am using this damned thing!"

I wasn't concerned about the limited print run. I'd have to stay sober for weeks just to afford any postage at all. And the price of the kit was right. I don't recall exactly, but something under $15. Needless to say, I didn't have time for mail order. I caught the first subway out to a stop that was nothing more than a circle on the city transit map, some place in the wilds of Brooklyn where the nearest Sears was located.

It was only fitting that I should journey to a strange land to obtain such a marvel. When I got the kit back to the apartment I saw it came with a bag of gelatin, a flat tray for the gelatin, hecto pencils, and sheets covered with ink, resembling ditto masters. It wasn't a Golden Fleece, more like a Holy Grail. An instant publishing company!

I'll spare you a history of the purple prose I perpetrated by means of this device. A lot of what I wrote was rather like this essay. I've already wandered a long way from Poisoned Pen Press and the present and you're probably wondering what does this have to do with Julius Rosenwald?

The answer, as I only recently discovered, is that he was the man who turned Sears, Roebuck and Company into a retailing giant. When Julius joined the company in the l890s he began to diversify the product line of what had originally been a watch company and began selling everything a typical Midwestern farm household might need, from barbed wire to hectographs. (Well, I suppose he expanded the products even beyond what a typical household might need...)

If it weren't for Julius Rosenwald's business acumen, I would never have been able to buy the hectograph that enabled me to publish my fanzine, keeping my interest in writing alive, and so there would have been no Byzantine mysteries for Julius' great-grandson to publish. Or else they would have been solely written by Mary.

Julius Rosenwald was also one of the early 20th Century's most notable philanthropists. The Rosenwald Fund, established for the well-being of mankind, contributed to museums, black institutions, Jewish charities, and universities, colleges, and public schools. Its school building program aided in the construction of over 5,000 Rosenwald Schools and teachers' homes in the rural south.

All somewhat more important in the scheme of things than John the Eunuch.

(For more information check out this article at the Sears Archives

Read/Post Comments (3)

Previous Entry :: Next Entry

Back to Top