1481889 Curiosities served

The Case of the Missing Bees

Previous Entry :: Next Entry

Read/Post Comments (8)

When I got over the pain and the stinger had been extracted and the wound coated with merthiolate, I felt sorry for the bee because after stinging they die. And unlike wasps, hornets and yellow jackets, honeybees aren't usually aggressive. Stepping on them is about the only way you can goad the peaceful laborers into hurting you.

Even though I live in the countryside, I rarely see honeybees these days. Their numbers seem to have been dwindling for years and according to a Reuters story, Vanishing honeybees mystify scientists, even commercial beekeepers are being affected:

Go to work, come home. Go to work, come home. Go to work -- and vanish without a trace.

Billions of bees have done just that, leaving the crop fields they are supposed to pollinate, and scientists are mystified about why.

The phenomenon was first noticed late last year in the United States, where honeybees are used to pollinate $15 billion worth of fruits, nuts and other crops annually. Disappearing bees also have been reported in Europe and Brazil.

Commercial beekeepers would set their bees near a crop field as usual and come back in two or three weeks to find the hives bereft of foraging worker bees, with only the queen and the immature insects remaining. Whatever worker bees survived were often too weak to perform their tasks.

Aside from learning that bees are largely responsible for pollinating a third of our food, I was interested to read that "honeybee hives are rented out to growers to pollinate their crops, and beekeepers move around as the growing seasons change."

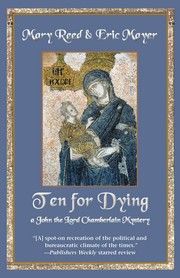

In Six For Gold Mary and I wrote about an itinerant Egyptian beekeeper who periodically loaded his cylindrical clay hives onto barges in order to follow the blooming of the flowers up and down the Nile. Ancient Egyptians were seeking to maximize the honey from their bees rather than to pollinate, but the principal was the same as used by traveling beekeepers today.

Mankind's artificial world changes rapidly. Smoking is no longer a habit taken for granted. Merthiolate isn't found in every medicine cabinet any more. Clover, which for a time was considered a luxurious and desirable ground cover, is now a hated enemy of lawns, targeted for death by specially formulated herbicides.

However, we can't yet design bees that don't need pollen, or fruit that doesn't require pollination, so beekeepers are still the nomads they have been for thousands of years. It can't be good news for us that their bees are vanishing.

Read/Post Comments (8)

Previous Entry :: Next Entry

Back to Top