Thinking as a Hobby

3478527 Curiosities served

Deceptive Chimpanzees...Big Deal

Previous Entry :: Next Entry

Read/Post Comments (0)

The researchers performed a set of experiments in order to attempt to demonstrate that chimpanzees "sometimes attempt to actively conceal things from others." In their introduction, they say:

Human beings sometimes attempt to deceive one another. Whereas various related but non-mentalistic phenomena such as bodily camouflage are widespread in the animal kingdom, intentional deception - in which one individual attempts to actively manipulate what another experiences cognitively - is considered by many to be a uniquely human cognitive ability.

That's the opening, and they're already saying dicey stuff, before we even get to the experiments. Surely there are grades of deception between an insect evolved to look like a stick and a man telling his wife he has to work late so he can shtup his secretary? Psychologist Robert Mitchell identified four levels of deception:

1) Simple camouflage (e.g. the insect that looks like a stick)

2) Active deception (e.g. a species of firefly that mimics the light flashing pattern used as a mating signal for another species in order to lure males in order to eat them). The behavior is "hard-wired" and inflexible.

3) Active and adaptive (e.g. Piping plovers lead predators away from their nest by pretending to have an injured wing, often exaggerating the behavior if predators start to lose interest).

4) Psychological sophistication (e.g. Telling your wife you have to work late so you can shtup the secretary). Can be entirely learned and extremely adaptive, and tailored to the psychological make-up of the target.

So Hare et al. already stack the deck by making the question simpler than it seems, telling us there are two kinds of deception: camouflage and "actively manipulating what another experiences cognitively." But that second category seems awfully broad, doesn't it?

Anyway, onto the experiments...

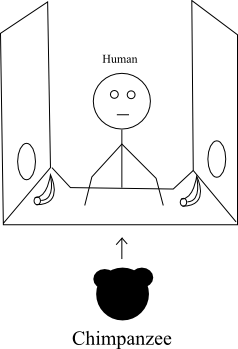

They experimented with 8 chimpanzees. In each condition, the chimp was coaxed to a display like the one below by the presence of a juice tube in front of the booth.

A human experimenter (E) sat in the plexiglass booth. On either side, tasty food like bananas were set near holes cut in either side, so that the chimpanzee could move to either side and take the fruit.

There were some early trials just to acclimate them to the environment and teach them that E was not a caregiver, but a competitor who would remove the food if the chimp either approached the food or waited over 5 seconds. Then several tests were done under various conditions:

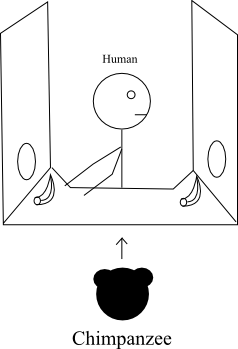

Body Orientation: In this condition there were two orientations, one where E's body and face were oriented toward one piece of fruit, and one where E looked toward one piece of food while E's body was oriented toward the other piece of food (shown below).

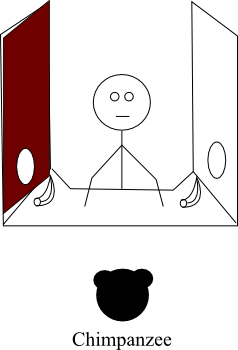

Occluder: There were several variations of this condition, but the simplest involved putting up an opaque surface on one side so that E could not see the chimp approach from that side.

So what do you think they found? Basically that chimps tended to approach the side where E was less likely to see them approach. If E was facing one piece of fruit, they tended to approach from the other direction. If there was an occluder, the chimps tended to approach from that side. In some cases, the chimps tended to take an indirect approach, first moving further away from the side E couldn't see before moving in for the food. In these cases, they used an indirect approach when E could see them moving further away, indicating that the chimps were trying to fake E out.

But what have they really demonstrated here? Thankfully they didn't go overboard in claiming something spectacular in their discussion of the results. They admit that it's difficult to really know what's going on. However, they do reject the notion that the chimpanzee is just using visual cues in the environment. They spend a lot of space trying to refute the idea that the chimp is using a strategy such as "approach in a way that I can't see a competitor's eyes or face." Their argument is based on a double-occluder condition in which there is an additional set of occluders with one side lower than the other, so that the chimp could approach from either side without seeing E's face. But since one side is lower than the other, they would be much more likely to see E's face, and this seems like a very weak argument for ruling out a visual-cue-based strategy.

And really, this seems kind of a paltry form of deception. Let me introduce you to the Portia genus of jumping spiders, predators with 8 eyes, excellent eyesight, and much more sophisticated deception than what the chimps showed here.

Among the myriad ruses employed by the cunning Portia is the selective use of environmental smokescreens. In other words, when the opportunity presents itself, Portia uses wind, dropping leaves, or the presence of any environ mental "noise," including movements by other animals to disguise its own stalking motions on the web of a prey spider. Given the presence of an environmental smokescreen, the stalking Portia moves farther and more quickly on a prey spider's web than in still conditions, Wilcox said.

The use of environmental smokescreens is not uncommon in predator-prey interactions, but Portia is the first arthropod described as using this strategy.

Even more exciting, however, is the compelling evidence that Portia is capable of initiating its own smokescreen signals, Wilcox said, a behavior never before reported in any predator.

Portia also seems able to mimic such environmental "noises" as a leaf or raindrop to simultaneously mask its presence and forward motion on the web.

Portia also mimics desirable calls of other spider species, and when encountering an unknown species, it randomly tries calls along a spectrum, honing in on the right frequency when it proves effective. They also take elaborate paths to prey, often approaching from behind.

So the researchers demonstrated that a chimp has deception skills not even really up to par with certain types of spiders. I have to say I'm underwhelmed.

This isn't necessarily to blame the researchers. I think this is the catch-22 of behaviorism. It's extremely difficult to make inferences about mental states based solely on outward behavior.

Hare, B., Call, J., Tomasello, M. (2006). Chimpanzees deceive a human competitor by hiding. Cognition, 101(3), 495-514.

Read/Post Comments (0)

Previous Entry :: Next Entry

Back to Top